The ‘refugee crisis’ these days is most often spoken about as a European issue but is in fact a global tragedy for many millions of families in every region of the world. But what is a refugee? What’s the difference between a migrant, an asylum seeker, an IDP (Internally Displaced Person) and a refugee? What systems and agreements does the world have to cope with the movement of people and are those systems fit for today’s connected world? Who and where are the people on the move and what policies could give them the help they need, and secure public and political support at a time when attitudes are often an uncomfortable mixture of compassion and fear?

People leave their homes for many reasons – to seek opportunity, to flee poverty, conflict, persecution and discrimination, to save and protect the lives of their families. Their journeys are usually traumatic and dangerous, moving from the unsafe to the unfamiliar, and sometimes they never reach the safety and security they are seeking. Sometimes they cross international borders but very often they are unable to escape their own country or prefer to seek safety in a more familiar environment. Sometimes they are able to find shelter with friends and family, but often they end up in tented camps or urban slums where their living conditions vary between basic and appalling. Some migrate for positive reasons – to experience different cultures, to travel and to take up interesting job opportunities, but here I am focusing on those who migrate because they feel it is simply too dangerous to remain at home. Very few of us would suffer the dangers and indignities of such migration if we felt we had any other viable choices.

Let’s look at some definitions and then at the numbers. A “migrant” is any person moving (across an international border or within a State) away from their home for any reason or duration. The UN refugee agency (UNHCR) talks about “forcibly displaced people”, who are the subset of migrants who move because they feel they have no alternative. The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) defines “forced migration” as “movement in which an element of coercion exists, including threats to life and livelihood, whether arising from natural or man-made causes”. This includes displacement due to famine or natural disaster as well as war and persecution. Such forcible displacement may be within a country (“Internally Displaced Persons” or IDPs) or across international borders. Refugees are the particular subset of forced migrants who have crossed an international border fleeing armed conflict or persecution. Refugees are entitled to legal protection (or ‘asylum’) under the terms of the 1951 UN Refugee Convention. An ‘asylum seeker’ is a person who has made a claim to refugee status but is awaiting a decision by the host country.

Public, political and media debate often unhelpfully confuses these terms, and indeed the reality is confusing. The lines are blurred. Poor nutrition is a factor in half the deaths of children under 5 – more than 3 million a year. If your children are suffering from life-threatening under nutrition, but where the specific definition of famine is not met, and you feel you have to move to a place where you can get emergency food, you may not meet the criteria for “forced migration” let alone refugee status, though it would be hard to deny an “element of coercion” applies. The bottom line is that simple desperate poverty, even if you are likely to die of it, doesn’t feature in these definitions – you are an ‘economic migrant’ – a term often used to dismiss someone’s need for assistance.

Whatever the reason, fleeing across international borders can be very risky. Countries bordering conflict zones vary in their welcome and in the prospects they offer to new arrivals, who often understandably want to keep moving on to find somewhere that can offer more hope of a better future. This is where the people smugglers see an opportunity to extort huge profits from desperate and vulnerable people, often by telling lies about the ease of the journey ahead or the help they will receive when they reach their destination. And nowadays many of the people making these desperate journeys are carrying mobile phones, which facilitate the smugglers’ work and offer attractive images of life in developed countries.

The conflicts in Syria and Iraq, in Afghanistan, in Yemen, South Sudan, Nigeria and elsewhere, the appalling drug and gang related violence in Latin America, and the discrimination faced by ethnic and religious minorities such as the Rohingya in Burma all add up to a world facing an unprecedented global challenge of forced migration and displacement, while more and more countries are closing their borders and turning away those seeking protection without even assessing their claims as required by international law.

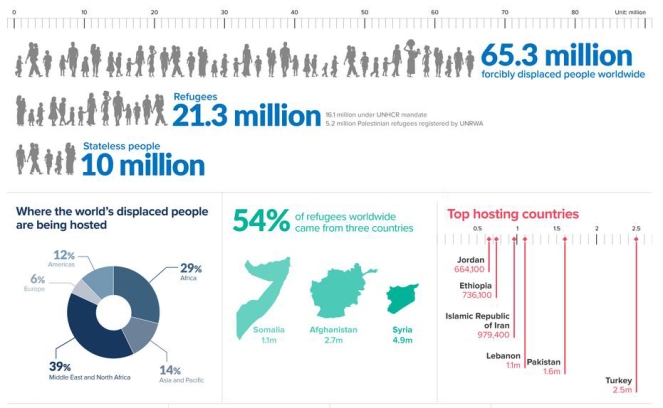

In 2015, the number of international migrants worldwide – people residing in a country other than their country of birth – was the highest ever recorded, at 244 million. 2015 also saw the highest levels of forced displacement globally recorded since World War II, with a dramatic increase in the number of refugees, asylum-seekers and internally displaced people across various regions of the world – from Africa to the Middle East and South Asia. According to UNHCR war and persecution have driven more people from their homes than at any time since records began, with over 65 million men, women and children now displaced worldwide. One in every 113 people on earth is either an asylum-seeker, internally displaced or a refugee. The vast majority of the world’s refugees – nine out of 10 – are hosted in low or middle income countries, led by Turkey, Pakistan and Lebanon. Half are children, and half come from just three war-torn countries – Syria, Afghanistan and Somalia. In 2015, 34,000 people a day were forced to flee their homes because of conflict and persecution. 2015 was also the deadliest year for migrants with 5,400 migrants worldwide estimated to have died or gone missing.

While the whole of Europe received 1.2 million asylum claimants in 2015, the vast majority of those forcibly displaced continue to be hosted by developing countries far less economically able to cope. Africa and Asia host 13.5m refugees. We are seeing the emergence of city-sized semi-permanent refugee camps in the deserts of Jordan and Eastern Kenya where lives are often lived in the face of constant danger, poverty and hopelessness despite the admirable resilience which refugees so often show. I have visited both places and their existence, while providing a measure of basic protection, is a blot on the conscience of humanity which we can’t leave to fester indefinitely.

Despite the immensity of this human suffering, searching for safety and protection is increasingly perilous. In the words of UNHCR ‘At sea, a frightening number of refugees and migrants are dying each year; on land, people fleeing war are finding their way blocked by closed borders.’

We are living in a world which, despite huge development progress, is wracked by conflict, disgraced by violations of human rights and disfigured by poverty and suffering, all driving people to desperate means to seek safety and security. Yet the warmth of welcome and the protection and compassion on offer is sadly and apparently increasingly compromised. Even children, often facing hazardous journeys alone, seem to be unable to move us to the action needed to ensure the protection and care to which they are entitled. What then should be done?

There are three levels of solution. First prevention of the causes of flight, second the provision of safe and legal routes for those forced to move, and third the care and protection on the journey and in the country of destination.

The ideal and the priority must be to make the world a safer and better place, in which people do not feel forced to leave their homes to find safety and security. This means tackling poverty, disaster and conflict more effectively. The Sustainable Development Goals once again show the way. If we fail to meet those goals, the numbers fleeing poverty and natural disaster will only continue to rise. International aid has a vital part to play in securing the prospects and livelihoods of the poorest and most vulnerable. At the same time, aid and development efforts need to pay attention to governance, conflict prevention and disaster preparedness. Conflicts often have their roots in disputes over resources or in ethnic and religious divisions which are not resolved but exacerbated by those in power. Once conflicts do develop, the international community needs to find the means to bring them to an end quickly through diplomacy, sanctions or, as a very last resort, military intervention with international agreement (Iraq and Libya have been disastrous, but intervention in Sierra Leone has been seen as a success, while failure to intervene to stop genocide in Rwanda is broadly recognised as a mistake).

What is the alternative to pushing desperate families into the hands of cruel people-smugglers? Is there a way for the international community to find agreement on the provision of safe and legal means for forcibly displaced people to find their way to a safe country? Does the 1951 Refugee Convention need updating? Probably, but there is fear that opening that discussion could lead to a weakening rather than strengthening of protection. Perhaps there needs to be a new “protocol” added to the Convention, without opening up its essential heart. Could there be a new obligation on states to ‘burden share’ by accepting planned numbers from defined countries in crisis based on their capacities? It can’t be fair that some of the world’s poorest countries are hosting the greatest numbers of refugees while the rich world increasingly seeks to close its doors. There has to be a better way!

Finally, the 1951 convention principles, together with those of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and other human rights agreements need to be applied effectively and with compassion. It is not acceptable for any asylum seeker to be sent back across borders, or refused admittance, without a proper individual assessment of their entitlement to protection in accordance with internationally agreed standards.

So what do these principles mean for action by the UK Government? We could start with the following:

- Maintain our commitment to 0.7% of GNI in international aid. This contribution is vital to prevent the drivers of forced migration, as well as to ensure achievement of the Global Goals. An appropriate proportion of this aid budget needs to be allocated to supporting governance, addressing climate change and preventing and mitigating disasters and conflicts. We must maintain our admirable record as a provider of emergency aid to lessen the impacts of conflicts and disasters and to support neighbouring countries hosting large refugee populations. By doing so we also have the authority to work to persuade other countries to do the same.

- We need to continue to play our part as a permanent member of the UN Security Council in addressing and resolving conflicts, supporting the UN’s peacekeeping efforts and ensuring that military intervention only happens with proper international agreement.

- The UK has decided to provide safe and legal routes for 20,000 vulnerable Syrian refugees over 5 years. This is welcome, but the number is pathetically small! We can surely do very much better. Perhaps we could start by increasing that number to, say, 100,000. Oxfam has called for rich countries collectively to accept 10% of Syrian refugees – close to half a million – by the end of 2016. Their calculation is that a “fair share” for the UK would mean admitting 23,982 this year.

- Despite Brexit, the UK needs to maintain its diplomatic engagement with Europe, as well as more broadly. The failure of the EU to reach a progressive consensus on dealing with the migration crisis in Europe is not something the UK can ignore. We are already seeing migrant boats attempting to cross the English Channel and we know that many migrants speak English and see the UK as their destination of choice. The scandalous situation in Calais is a reminder that we are a part of this, whether we like it or not. We need also to be part of the solution and that can only be found through international co-operation.

- There has been considerable pressure on the Government to accept a greater number of vulnerable child refugees, and rightly so. To date the response has been reluctant and shamefully slow. By December 2015 one in three migrants reaching Europe was a child and 40% of those now stranded in Greece by Europe’s failure are children. Unicef says that “throughout their journeys, refugee and migrant children suffer terribly, stranded at borders, forced to sleep in the open, exposed to rain and heat; left without access to basic services, and easy prey for smugglers and traffickers”. In 2015, more than 95,000 unaccompanied or separated children registered and applied for asylum in Europe. Of all refugees and migrants, unaccompanied and separated children are among the most vulnerable to violence, abuse and exploitation. Interpol estimates one in nine is unaccounted for or missing. How can this have been permitted to happen? The UK Government’s belated response has been to offer to resettle 3,000 vulnerable and refugee children at risk and their families from the Middle East and North Africa region by 2020 and to work with local authorities to resettle some unaccompanied and separated children registered in Greece, Italy or France before 20 March. They have also committed to accelerate family reunion of child refugees under the Dublin III regulations but the process is still far too slow and inflexible. Unicef’s recommendations (below) need to be implemented with real urgency.

Refugee and migrant children are in danger every day in Europe. If they have close or extended family members in the UK they should be reunited without delay. The best interest of a vulnerable child must be the primary consideration in decision making. This applies especially forcefully to those unaccompanied children languishing in the squalid camps in Calais and along the Channel coast. Unicef’s report ‘Neither Safe Nor Sound’ (http://www.unicef.org.uk/Latest/Publications/Neither-Safe-Nor-Sound/) describes the horrendous dangers encountered by these children, facing exploitation and abuse of the most heinous and vicious kind on a daily basis on the shores of two of the world’s richest countries. It should be essential reading for the newly appointed Ministers in Theresa May’s Government and they should act on its recommendations as a matter of greatest urgency, as should the French Government. Both are failing in their obligations to protect vulnerable children and to act in their best interests. It is shameful and it must change. There can be no excuse for inaction. Every day lost is one more day of abuse faced by children in danger.

Finally, we must change the narrative of our national (and international) conversation about refugees and migrants. Rather than focusing on keeping numbers down regardless of who they are, where they come from or why they come, we should work to share understanding about the different types of migrant and make an effort to use the correct language. This applies to all of us, but especially to the media and politicians. Let us put our compassion and humanity at the forefront of the discourse, especially about those who have been forced from their homes by horrific circumstances that few in the UK could ever imagine facing themselves. If they did, they would look for warmth and welcome and kindness and empathy. Let those be the principles and values with which we approach policy making as we seek to play our part in addressing the global crisis of forced migration.

Definitively David. We need a ´A better world for refugees´. Have an amazing weekend!

LikeLike