A great deal has been written and discussed over the last two decades and more about the emerging challenges facing International Non-Governmental Organisations (INGOs). This crisis has multiple dimensions, but centres around issues of the power relationships between INGOs based in the “West” or “Global North” and the communities and local, regional and national organisations based in the low- and middle-income countries of the so-called “Global South”. The power dynamics also include the role of donors, philanthropists, Northern Governments, and international institutions such as UN Agencies and Multilateral Development Banks. Linked to these power dynamics are issues of organisational legitimacy, values and effectiveness, as well as media scrutiny associated with questions such as safeguarding, executive salaries, and the existence of racist attitudes and behaviours in INGOs.

Entire books have been written about this and it is far too complex to try to cover every aspect of the debate in a short artcile. However, in my consultancy work for international development/humanitarian organisations I have frequently been called upon to offer advice on how INGOs might build their strategies and examine their organisational structures and governance to address these power-related issues in the context of a rapidly changing operating environment.

These questions and challenges do not only apply to INGOs working in the field of international development and humanitarian action but have resonances for any organisation that seeks to conduct or support work across multiple territories and cultures or to operate in sectors where individuals and communities face discrimination, disadvantage, oppression and denial of their human rights.

In this article, I want to focus on just one narrow but fundamental aspect of this set of questions, ie what options do INGOs have to (re)structure themselves so that they can maximise their legitimacy and positive impact while contributing in solidarity to addressing the power imbalances that are both the reason for their existence and their greatest challenge.

Terms like “localisation” and “decolonisation” are frequently used but not clearly defined or understood, and often seen and felt differently by the various stakeholders in the INGO sector, sometimes surprisingly – I have, for example, met some African INGO team members who fear that the localisation trend is simply another colonial power play to put all the onus on to them instead of the Global North actors taking responsibility for problems they have created.

These problems don’t have easy answers and anyone who comes to you with a simple off-the-shelf prescription is probably best avoided. Each organisation needs to find its own way, based on its history, culture, goals and relationships. It would be wise to consult widely and impartially, ideally supported by external facilitation

Nevertheless, INGOs may be able to learn from others who have chosen particular structural paths through the maze. For example, some INGOs have moved their global operations bases to the Global South; some have de-merged their country operations into independent local organisations; some have relocated specific organisational functions to different geographies; many have sought to ensure that their Boards are more representative of the communities with which they work. I have not found a clear set of blueprints and there is limited research, to my knowledge, about the effects of these different decisions on the key areas of legitimacy and effectiveness.

Based on my experience and research, I have not found a clear typology which spells out the structural options and considerations that an INGO might wish to consider in addressing these challenges. And of course, structure is only one part of the response – just changing the structure, without addressing organisational strategy, culture and values, for example, will not meet the challenges. I have tried to come up with a typology that INGOs may find helpful – not for them to simply choose a model from a menu, but rather to assist their thinking in coming up with the hybrid that is most appropriate for them. But before I come to the typology, I hope it may help to set out some of the key considerations that any organisation may wish to take into account when reconsidering their structure in this INGO context.

Key Considerations

- Accountability (which structures can enhance the INGO’s accountability to its key stakeholders, especially when different accountabilities may conflict, eg accountability to donors and to clients? Internal accountabilities are also relevant, eg country offices to HQ and vice-versa)

- Legitimacy (INGOs need legitimacy to raise funds, build partnerships and operate effectively. This derives from a variety of sources, including regulatory registration, legal compliance, public trust, donor requirements, local and international partners, efficiency and outcomes. Which structural models would most support an organisation’s legitimacy in the eyes of its key stakeholders?)

- Power and Control (where should ultimate control over various decisions and functions lie in the INGO? There is a clear direction of travel towards greater sharing and devolution of power in the INGO sector, but there may be costs to this in terms of efficiency, agility, bureaucracy and complexity)

- Managing Uncertainty (INGOs are operating in a time of considerable uncertainty, change and challenge, facing narrowing civic space in many countries, even within Europe, and often negative public opinion with respect to their objectives. Which structural forms offer the greatest agility, capacity to respond, innovate and adapt, and to support local civil society in the face of these challenges?)

- Technology (new communication technologies and tools to better capture and analyse data [including AI] allow more fluid intra-organisational exchanges. Do these technologies facilitate greater devolution and/or allow more effective relationships within a more unitary structure?)

- Governance (operational structures and governance structures are related but distinct. Both need to be considered together. Unitary models can have strongly representative Governance, and more devolved structures could have narrower governance. Both are important and ideally compatible with the organisational principles chosen)

- HR/employment (different structural models have implications for employees, culture, salaries and employment law. Are operational staff “on the ground” direct employees of a UK HQ or of a local entity subject to local regulation; is there a salary differential or hierarchy between “expat” and “local” staff? Would a change of structural model necessitate employment changes? How would the culture and relationships need to change and adapt? How would EDI policy and practice differ?)

- Balance of activities (Is there an associated shift between, for example, operations and advocacy? Does this imply a shift in the most suitable location from which such activities are managed?)

- Funding (do donors have preferences about structure and location that would affect structural choices, eg do they prefer to fund organisations based in their own country, or to fund directly those in countries of operation? In a devolved model, does each country have the potential to be self-funding or will there remain a dependence on transfer of resources from the HQ or dominant country, and how does this impact on power relations within the organisation?)

Structural models

There is no available agreed breakdown of structural models, terminology is not exact, and model descriptions are often unclear or overlapping. Nevertheless, there are a range of possibilities mentioned in the literature and these can be organised roughly along a spectrum of decentralisation, from centrally-controlled to completely devolved.

Note that even the frequently used term “decentralisation” can be subdivided (eg deconcentration (transfer of responsibilities without transfer of authority); delegation (transfer of responsibilities with the amount of authority necessary to discharge them); devolution (authority transferred to autonomous or semi-autonomous entities). Even within defined models there can be significant variation, depending for example, on organisational culture, variations in governance or use, or not, of a common brand.

Whichever structural model is applied, beyond a simple unitary one, will require some kind of negotiated (normally written and signed) agreement which specifies degrees of authority, autonomy and decision-making power that reside in different operational units, and rules and norms for interaction, financing, external communication and representation, brand licensing, dispute resolution and more.

There are many ways in which structural options may be categorised, but here, in summary (with more details below) is my attempt at a typology of structural possibilities which may help to inform debate. I have deliberately not given examples under each type as few organisations would precisely fit a given model, but I’m sure readers can think of their own. These are grouped into 5 groups:

- Unitary

- Unitary with country offices (“HQ-dominated”)

- Unitary with subsidiaries

- Group

- Franchise

- Federation

- Confederation

- Alliance

- Membership

- Member-led alliance

- Partnership

- Contracting

- Consortium

- Network

- Movement

- Platform

Unitary

Unitary structures are those in which a single legal entity, with a global headquarters or centre controls all aspects of the organisation, normally through a single Board. Staff are recruited, selected, managed and employed by the unitary organisation, regardless of their location. Activities are overseen from the centre, and accountability is to and through the centre and all funds and accounting flow through the centre.

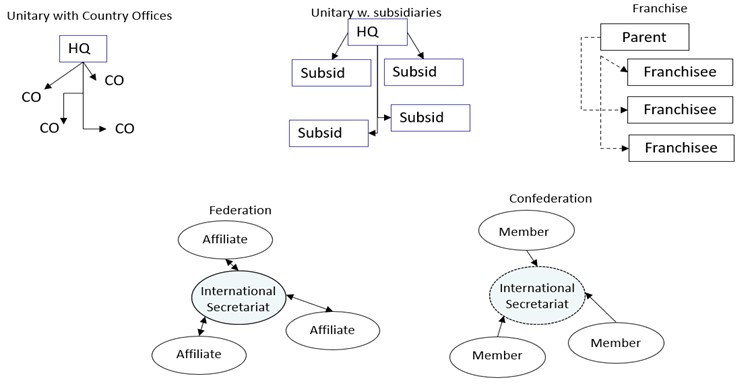

Unitary with country offices: unitary structures may operate through regional or country offices, which have delegated responsibility for managing staff and operations in their country. The degree of autonomy with which country offices function, and the amount of guidance or support provided by the centre, can vary widely but ultimate authority rests with HQ and country office leaders are normally expats directly employed by HQ. This has historically been the INGO norm, but less so now.

Unitary with subsidiaries: a unitary structure may operate through subsidiaries, in which case local offices are distinct legal entities, registered in their country of operation, but wholly owned, and ultimately controlled, by the parent, which is most likely their sole member or shareholder with the power to appoint members to their respective Boards. Leaders of subsidiaries could also be represented on the main Board. Depending on the nature of agreements, subsidiaries may have authority to raise and spend funds locally, initiate and implement their own projects. In some cases, subsidiaries may have their own sub-offices, perhaps even internationally.

Group

A group structure normally consists of a number of independent legal entities in different locations that share a vision, mission and goals, and often a brand. They operate under the terms of a formal written affiliation agreement which sets out the terms and limits of their collaboration, and the degree of accountability which they owe one another. They may establish, or be set up by, an international secretariat that facilitates their common strategy and relationships to ensure cohesion, manage relationships, resolve conflicts and organise consultations. They would each have their own Governance arrangements and normally be represented in the governance of the secretariat

Franchise: members of a group may operate under a particular type of affiliation (franchise) agreement whereby they operate as distinct legal entities, but their freedoms are strictly limited by a set of rules aimed at maintaining a common brand identity. The franchise agreement is normally under strong control of the parent organisation and could theoretically be withdrawn.

Federation: a federation is a group in which members cede power voluntarily to a relatively strong international secretariat, perhaps in exchange for the use of a common and powerful brand. Depending on the nature of the affiliation agreement, the international secretariat may have considerable powers in relation to the federated organisations.

Confederation: a Confederation is a group of autonomous, like-minded organisations working in a common field, each led by independent Boards, which team up to establish a small co-ordinating secretariat. The secretariat would be governed by the members, eg through a General Assembly and elected Board members.

Alliance: an alliance is a looser form of collaboration between a number of NGOs operating in closely related fields and sharing some facilities, expertise and strategies. It may not have a secretariat, but any central co-ordination may be based in one of the member organisations. The alliance may be long-term or time-limited to address a specific task or objective. It may carry out activities or campaigns under a common brand.

Membership

A membership structure has independent organisational members in different locations that would normally pay a membership fee in return for specified member benefits and in acceptance of membership obligations. They would qualify for membership based on a set of agreed criteria. The central organisation may be the initiator of the structure or may be established by a collaboration among the members. Scientific organisations often have this structure. Governance of the common activities, including decisions on admission or expulsion of members, membership criteria, common activities etc would normally be through election of member representatives to the Board of the umbrella organisation

Member-led Alliance: in many INGO structures there is a strong HQ/centre with a variety of relationships with entities that manage implementation of programmes at country level. A member-led alliance operates in reverse, where the international secretariat is managed and controlled by the country-level members, though this doesn’t necessarily mean that the HQ is small or powerless. However, they may agree to cede certain powers to the International Secretariat and national members may, for example, agree to contribute funds to enable the secretariat to function. This secretariat may be larger than any of the members and may itself have national or regional offices operating under its auspices.

Partnership

Less formalised than group or membership structures, partnerships may be formed to enable autonomous organisations to work together for a common purpose and/or to bring greater power and authority to an enterprise. They would operate under a partnership agreement. Effective partnerships are built on mutual trust and respect and a shared vision, with defined and agreed roles and normally a level of equity or parity between the partners. They would reap mutual benefits, but also share risks. The partnership is probably not a distinct legal entity with its own governance but governed instead through joint meetings between the partners. There would not normally be a shared brand.

Contracting: a particular form of partnership may be where one partner contracts others to undertake activities on its behalf, in which case there is less equity in the relationship, which is more transactional, and likely to be time-limited

Consortium: a consortium is a particular type of partnership where organisations join together to undertake a specific set of activities. In the international development world, many contracts with donor agencies now require INGOs to join consortia in order to be eligible to submit bids for contracts or grants. Although such arrangements are often temporary and fluid, they can lead to more concrete and long-term partnerships.

Network

A network is the loosest form of INGO structure, through which organisations work together through normally relatively informal arrangements, usually (though not always) lacking a central secretariat or a common brand. But they may persist for a long time and can be relatively stable. In networks structures, there are fluid collaborations between members, information sharing through newsletters and mailing lists, and joint-activity planning through irregular gatherings.

Movement: a movement is perhaps an even looser form of network, which may have only a very limited formal structure, but with which different groups identify and act in accordance with their understanding of the movement’s goals. Some may have organisations that bear the movement’s name, but these have little, if any, control over activities carried out in that name.

Platform: a platform in this context is an online platform which allows individuals and organisations to initiate or support activities (often referred to as “clicktivism”). They may raise funds and have some organisational existence, or facilitate individuals to transfer funds to overseas projects. Or they may be far more informal, effectively memes spread through social media which drive action.

A diagrammatic representation of some of these structures might look like this (arrows indicate direction of decision-making or control. Boxes indicate distinct legal entity):

Discussion

Few organisations adopt any single one of these organisational forms or structures, but often combine elements of several in hybrid forms.

There is no “right” answer to these structural questions. Every option involves compromises and trade-offs (eg greater decentralisation may bring the benefits of greater responsiveness to local conditions, share power, and enhance legitimacy in programme countries, but may also bring a degree of fragmentation or lack of cohesion and reduce the efficiency of decision-making)

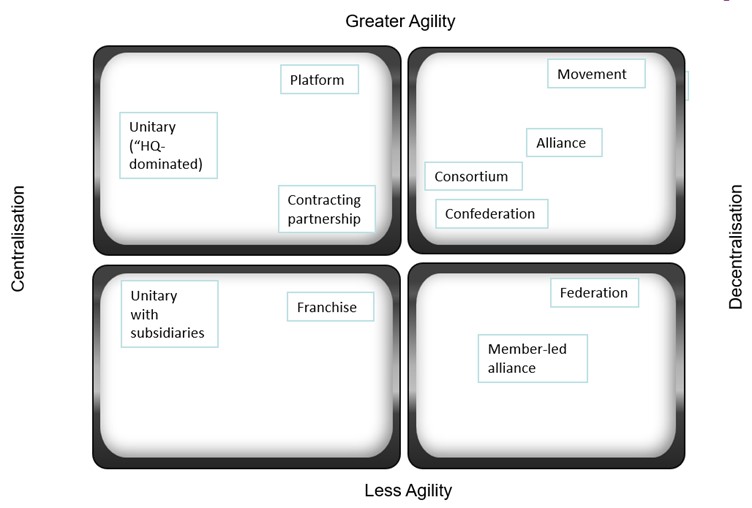

Any INGO needs to decide which considerations are most important to it and balance these against the downsides and risks that may arise from maximising such considerations. See for example the Boston Matrix below (others could be constructed using different key considerations for the axes)

The literature highlights the issue of agility as perhaps the most vital consideration in today’s ever-changing and volatile context, albeit largely based on big international development INGOs. This is based on the perception that INGOs are facing multiple challenges to their legitimacy and funding amid geopolitical turmoil and a range of uncertainties. Their priority is to be able to adapt quickly as circumstances change (which they are not currently very good at). At the same time, they are facing the pressure to “localise”, “decolonise”, transfer power to the Global South. But these priorities of agility and localisation may be in tension with each other. How to resolve that tension (eg through communication, consultation, governance and culture) is perhaps their key organisational challenge.

The following matrix seeks to place the various structural models within a framework of agility and decentralisation. The placement of each model within the matrix is a matter of judgement and could well vary depending on how each organisation manages the model in practice. Organisational culture, governance arrangements and communication mechanisms can fundamentally alter the degree of agility of a given model. And this is only one possible matrix among many.

Conclusions

In the light of the increasing challenges to the underlying assumptions on which (particularly Western) INGOs have been built, it is an important time for leaders to review and refocus, so that they can more effectively exercise their solidarity with people and communities facing poverty, exclusion, exploitation, conflict and crisis. Each INGO needs to decide on its own structure in the context of a wide range of related considerations, to ensure that the structure is consistent with its strategy, culture and ethos, that it is clear about the objectives of structural change, and that it can gain the support of as many of its stakeholders as possible through a process of genuine consultation and listening. Whatever the chosen structure, each organisation will need to ensure that it works hard within that structure to deliver on the goals it has set, with a particular focus on power relationships, equity, diversity, inclusion, anti-racism, safeguarding, and clarity about its approach to localisation. Changing the structure does not answer these questions on its own – it is a means not an end in itself. Working alongside independent consultants can help in many ways, not least in facilitating consultations which allow for a diversity of views to be expressed, confidentially where appropriate.