Famine is a word with enormous power. It conjures intense and emotional images and brings to mind momentous events from history. Depending on our age, we will recall the tragedies of Biafra, Bangladesh, Cambodia or Ethiopia, or perhaps China or India. People in the humanitarian field are very sensitive to the use of the “f” word, wishing to avoid any perception that they may misuse its power to raise funds when the reality is not as bad as the word may lead us to believe. But I’m concerned that this reluctance may have gone too far. Are we now so careful that we are failing to warn of devastating food crises until it is too late for many of those affected? The international humanitarian community now applies a very precise and detailed definition of famine which requires verifiable and extensive data before famine can be declared – data which is often impossible to gather in the conditions of conflict and crisis in which famine is most likely to occur.

I recall the crisis in Somalia in 2011. Aid agencies had been warning for months of a severe food crisis arising from a combination of drought and conflict, but it was hard to get the media attention that was needed to drive the essential fundraising effort to ensure help could reach those in most desperate need. Famine was finally declared in July 2011 and this drew the attention that facilitated a larger scale response. But it was already too late to save the lives of hundreds of thousands. A subsequent study showed that nearly 260,000 people died. In the worst affected Lower Shabelle region 18% of children under five died. A spokesman for the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) said “responding only when the famine is declared is very very ineffective. Actually about half of the casualties were there before the famine was already declared.” When I visited Southern Somalia in September 2011, I met families who had already been on the road since before famine was declared and who would probably not have made it to the Kenyan border without the help UNICEF and partners were able to provide inside Somalia. They were hungry, exhausted and destitute, and their stories moved me more than anything I have seen and heard in a lifetime in the development field.

Why do we still wait so long before we respond on a sufficient scale to prevent famine? There are many reasons. There is simply not enough money to meet all the world’s humanitarian needs. As of the end of November 2016, only $11.4 billion had been made available out of a global humanitarian appeal for US$22.1 billion to meet the needs of 96.2 million crisis-affected people in 40 countries.

Donors and agencies are constantly struggling to prioritise when every decision means life and death. It is near-impossible to gather the necessary data in conflict-affected areas. Host country Governments often don’t want to admit that there is a food crisis, even less a famine or impending famine, and the lack of a free press can mean independent voices are stifled. Politicians and donors are still to a considerable extent driven by the media – if a crisis takes off as a media story, help is more likely to be found. Hence aid organisations may be tempted to focus on the worst stories they can find to get the attention of the media. They know the power of the “f” word in that context but don’t want to open themselves to accusations of exaggeration. Even when they know that famine is possible in the absence of sufficient immediate humanitarian assistance, they are reluctant to use the word.

So what is the definition of famine and when can we use the “f” word? There have been many definitions throughout history, but the humanitarian community now uses the IPC Integrated Food Security Phase Classification, which defines 5 ‘phases’, summarised in the following table:

According to the IPC, ‘famine exists in areas where, even with the benefit of any delivered humanitarian assistance, at least one in five households has an extreme lack of food and other basic needs. Extreme hunger and destitution is evident. Significant mortality, directly attributable to outright starvation or to the interaction of malnutrition and disease is occurring’. Significant mortality means 2 people dying every day for every 10,000 of population. For a city the size of London this would mean nearly 2000 deaths every day. The IPC recognises that areas are declared to be in famine only when substantial deaths have already occurred and action taken at this stage will be too late to save many lives. The IPC therefore also provides guidance on the minimum evidence required to project a famine or to declare an ‘elevated risk’ of famine. The latter can be used when there is a lack of reliable data in all the relevant categories. The full Guidelines can be found at http://www.ipcinfo.org/fileadmin/user_upload/ipcinfo/docs/IPC_Famine_Guidelines_Nov16.pdf .

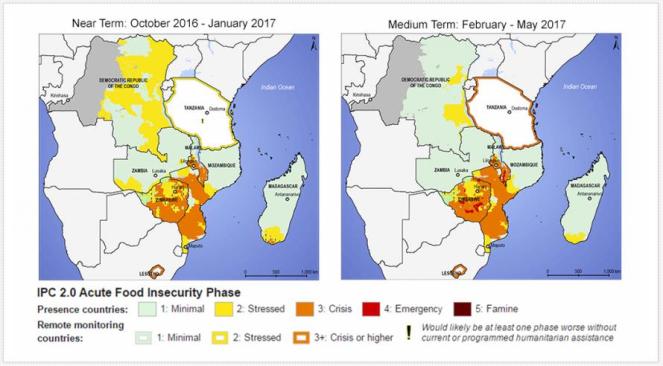

Unfortunately it seems that only a full famine declaration is likely to attract the necessary attention and resources for a full-scale effective response. Today there are three places in the world where the ‘f’ word could legitimately be used. But we hear far too little about any of them. And there is now also a fourth area where IPC phase 4 is likely to be present. The following map from FEWS Net highlights these 4 areas in red: North-east Nigeria, South Sudan, Yemen, and parts of Southern Africa affected by El Nino drought.

A special report on Nigeria published by FEWS Net on 13th December stated that ‘a Famine likely occurred in Bama LGA and may be ongoing in inaccessible areas of Borno State’. The report goes on to say that ‘the risk of Famine in inaccessible areas of Borno State will remain high over the coming year. Given current levels of food insecurity, significantly below-average crop production, disrupted livelihoods, and very high staple food prices, millions of people are likely to remain severely food insecure over the October 2016-September 2017 consumption year’ and the current response is insufficient. The most affected populations are those without humanitarian assistance in inaccessible areas and people displaced by the ongoing conflict (IDPs). IDPs in the northeast region are estimated at 1.8 million, of which 1.4 million in Borno State.

For South Sudan, an IPC Alert was issued in June which included the following: “Although Famine is not declared at this time, either at State or County Level, the risk of famine is still looming in parts of Unity State (Leer, Mayendit and Koch) where conflict and other factors can quickly and dramatically escalate’.

In Yemen, around 2 million people face a food emergency (IPC Phase 4) and some populations could face Catastrophe (IPC Phase 5)(the same phase classification as Famine but affecting some households rather than being widespread across an area of at least 10,000 people). The UN’s World Food Programme has used the ‘f’ word, stating that ‘millions of people are on the brink of famine’. WFP adds that ‘the lack of immediate and unhindered access to people who urgently need food assistance – compounded by a shortage of funding – means that famine is a possibility for millions of people, mostly women and children who are already hungry in this war-torn country.’

In Southern Africa the long term impact of earlier El Nino droughts means increasing populations, particularly in Malawi and Zimbabwe, are likely to be pushed into Phase 4 Emergency conditions during the ‘lean season’ of January to March, when food supplies run low prior to the next harvest and food prices increase. The earlier droughts mean this lean season will be accentuated as we move into 2017.

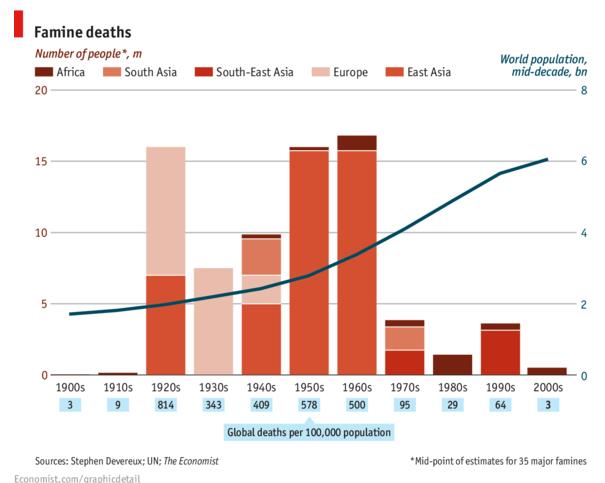

The 20th century was one in which an estimated 70 million people perished in 35 big famines, nearly half in China’s Great Leap Forward of 1958-62, and another quarter during Stalin’s forced collectivisation of the Soviet Union in the late 1920s and early 1930s (especially in Ukraine and Kazakhstan). The other huge famine was that in Bengal in 1943. As China, India and the former Soviet Union have made dramatic progress in food security, subsequent famines have occurred predominately in places where conflict and political instability has exacerbated existing challenges arising from drought. In spite of the high profile famines in the Sahel and the Horn of Africa in the latter half of the 20th century, deaths from famine have reduced dramatically even as global population has risen.

Yet, even today as we move from 2016 into 2017, we cannot afford to be complacent. We live in a world which is globally more prosperous than ever before in history, yet children still die from lack of food, especially where war adds to poverty and the increasing impact of climate change. Right now there are food emergencies currently or imminently affecting at least 5 countries. In Nigeria it is likely that famine exists now, even though lack of access doesn’t allow certainty. In Yemen and South Sudan, millions are on the brink of famine, and in the worst affected parts of Malawi and Zimbabwe millions more will be struggling to feed their children in the coming months.

Food crises are complex and the international community continues to debate the definitions. Yet the injustice remains clear. It is wrong that children should starve to death in a world which has enough resources to prevent it. It is wrong that, when prevention efforts fail, we can only find half of the help that is needed. If the ‘f’ word has the power to change that, then we should use it. We have not yet rid the world of famine. It exists today, in reality, and as a real and present threat in the lives of millions of our fellow citizens. It need not be so. We know what needs to be done to ensure that we never need to use the word again:

- Famine is most likely where there is war and conflict – the international community needs to do more to ensure that differences can be resolved through diplomacy and international law. We need to examine our national conscience in relation to the sale of the weapons that fuel such conflicts.

- Food insecurity is most likely to tip into famine where chronic malnutrition makes people vulnerable. One in 4 of the world’s children is affected by chronic malnutrition and over half in the worst affected countries. Over 150 million children under 5 are stunted by malnutrition. If we are to rid the world of famine, we first need to ensure that we tackle the widespread vulnerability of chronic undernutrition.

- Famine is also fundamentally a result of inequality. Even within countries, there can be huge disparities in access to livelihoods and food, while a global sufficiency of food still leaves people in the poorest countries vulnerable to crises that can bring millions to the brink of starvation, or beyond it. While the argument continues about how much a rich country like the UK can afford to spend on aid, it is abundantly clear that what we are providing is far too little – even the most clear and urgent needs are not being met.

- If we don’t tackle climate change we will not rid the world of hunger. Food and livelihoods are produced from the environment. Where environments are marginal and people are susceptible to floods and droughts and storms, climate change is decreasing their capacity to cope, meaning that any shock, be it environmental or conflict-related, is more likely to push them over the edge into hunger.

- Famine is a gross violation of human rights. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child Article 27 recognizes ‘the right of every child to a standard of living adequate for the child’s physical, mental, spiritual, moral and social development’. The right to adequate food is recognised in the UN’s human rights framework and a UN Special Rapporteur has been appointed to monitor compliance with this right which is ‘realized when every man, woman and child, alone or in community with others, has physical and economic access at all times to adequate food or means for its procurement’. States have a core obligation to take the necessary action to mitigate and alleviate hunger even in times of natural or other disasters.

The ‘f’ word really should be unacceptable – a true swear word that never needs to be uttered. Let’s hope we get there soon. Meanwhile, famine continues to threaten the lives of some of the world’s poorest and most vulnerable people. It does so because, apparently, we collectively just don’t seem to care enough to change that: to find our collective strength to end conflicts, to work together to tackle climate change, to deliver known solutions to chronic malnutrition or to hold states to account for their part in violating the human right to food.

2017 could be the year we finally decide to take the steps necessary to deliver on the SDG promise to end hunger by 2030. It depends on each of us doing what we can. Now that is a New Year’s resolution we can all make. Happy New Year!

Thanks David for another great thought piece. Fully agree with your points, though worth also reflecting on the flaws of an international response-system that relies almost entirely on voluntary contributions – and thus is totally dependent on media spot-light. In other areas of life we rely on tax or insurance-type mechanisms to pool risk and express solidarity…

LikeLike